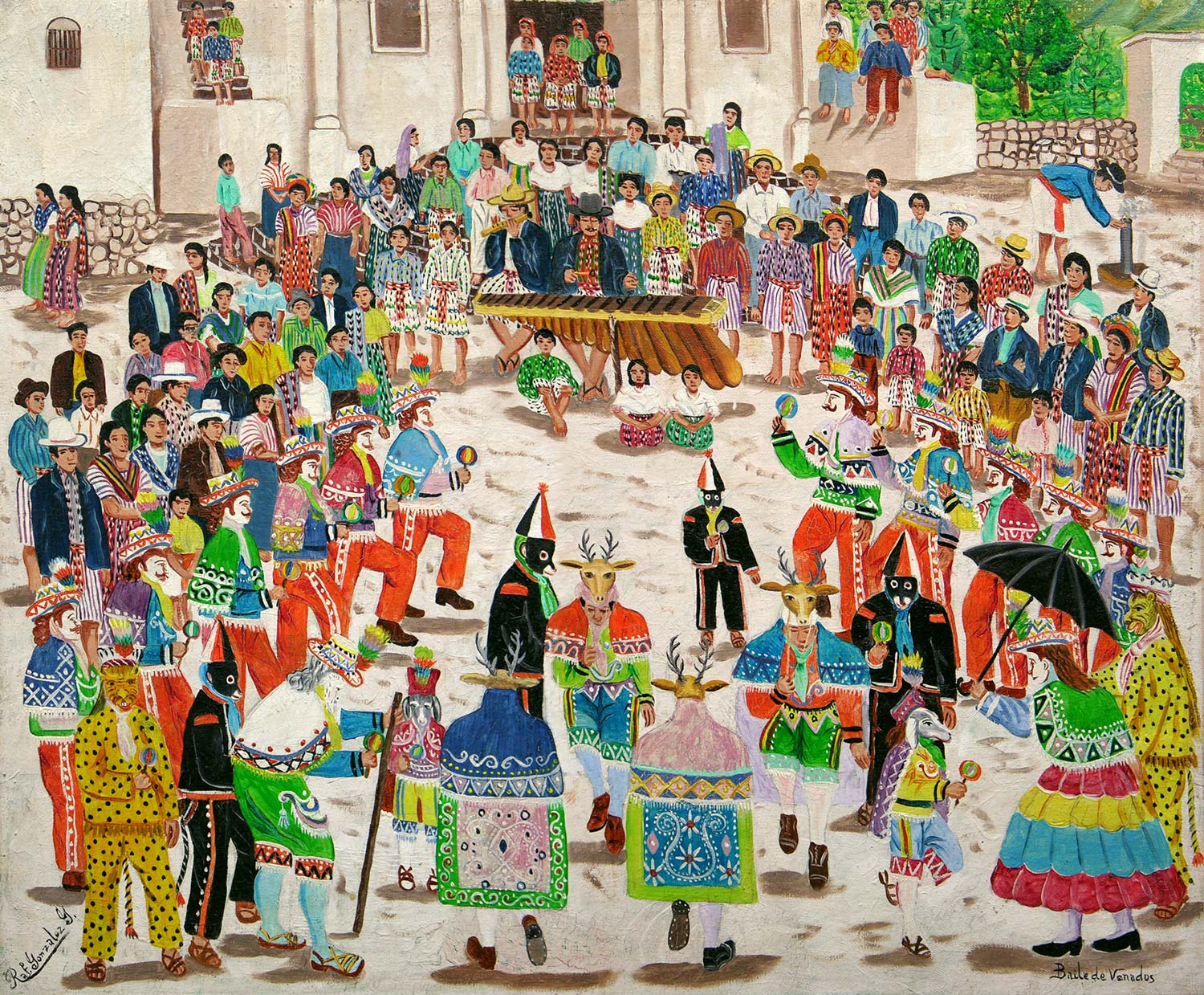

Two paintings illustrate the Deer Dance in different ways. The painting by Rafael González y González depicts the dance as performed in San Pedro la Laguna, while the one by Edwin Gonzalez shows the dance in Santiago Atitlán.

The Deer Dance, or Baile de Venado, is one of the oldest and most popular of the masked dances performed by the Maya. One of the few surviving pre-Hispanic dances, this dance exemplifies the passive resistance of the Maya to the invading culture. The ritual is based upon the Maya belief in the sacredness of all life forms. Lise Paret-Limardo de Vela, who undertook a survey of the Deer Dance in different Maya communities, wrote: “In ancient times, the Baile de Venado, or Venado, undoubtedly prior to the conquest, was a ritual hunting dance. Its object was to ask the divinity for permission before going out to hunt, to implore protection so that nothing bad happened to the hunters and, on certain occasions, to offer the carcass in sacrifice.”1 While the Deer Dance has deep pre-Hispanic roots, it became nominally Christian, most notably in the dialogue of the dancers and many of the costumes.

While both the Trocortesian Codex and the Madrid Codex, two of the four surviving Maya codices, have depictions of deer being hunted with traps, or being sacrificed to gods, we do not have any descriptions of the rituals or dances having to do with a deer hunt. Thomas Gage, a Dominican friar who travelled in Mexico and Guatemala between 1625 and 1637, gives us the earliest known written description of such a dance:

It was the old dance which they used before they knew Christianity, except that then instead of singing about the Saints’ lives, they sang the praises of their heathen Gods. They have another dance they often perform, which is a kind of hunt for some wild beast. …this dance involves much hollering and noise and calling one unto another, and speaking in a theatrical way, some relating one thing, some another, concerning the beast they pursue. These dancers are all clothed like beasts, with painted skins of lions, jaguars, or wolves, and on their heads such pieces as may represent the heads of eagles or other raptors, and in their hands they have painted staves, swords and axes, wherewith they threaten to kill the beast they pursue. The ancient Maya probably performed a deer dance before a hunt to ask for divine permission to kill the deer and for the safe return of the hunters. 2

After the Spanish invasion, many dances were forbidden by the Catholic Church because they were deemed heathen. New dances were created or imported, such as the Baile de los Moros y Cristianos (Dance of the Moors and the Christians) or Baile de Conquista (Dance of the Conquest), which did not offend the priests. The dances that did survive ultimately had to conform in some way. Although there were churches in every town, there were not always resident priests in the smaller towns, and they did not always speak the local Maya language. These factors allowed some ancient Maya beliefs and traditions to survive within the dances, somewhat adjusted, under the cloak of Christianity. Of the pre-Hispanic dances that did survive, the Deer Dance is the most popular and well documented. In the early 1990s, the dance was still being performed in at least forty-five different Maya towns.

The form of the deer dance varied in different towns, often subject to how tolerant the local priest was of Maya customs. In these two paintings of the deer dance, we can see the tradition in two neighboring towns: Santiago Atitlán and San Pedro la Laguna. In Edwin Gonzalez’s painting, the performers in Santiago Atitlán dress in deer skins and wear masks to which antlers are attached. This is visually closer to what Thomas Gage described. The San Pedro depiction by Rafael González y González shows the dance as it would have looked around 1940, with the deer and other dancers wearing elaborate capes that would have been influenced by European fancy attire. Edwin González’s intricately detailed watercolor of the Deer Dance in Santiago Atitlán probably was based on a black and white photograph taken in the early part of the twentieth century.

In San Juan Comalapa, Lise Paret-Limardo documents the existence of two different Deer Dances, the Chitimazat and the Calanmazat. The Chitimazat was the older deer dance. The performers in the dance were two old men, two deer, a jaguar and a dog. Only experienced hunters participated in the dance. The deer dancers dressed in deer skins and the jaguar dancer in a jaguar skin. Paret-Limardo writes: “Incense and candles were burning in front of the table. Before this altar, all the hunters paraded, one by one, recollecting the scenes of the hunt, citing the names of the mountains and places where they had passed to hunt; they also asked that nothing happen to them during the dance.” In the nineteenth century the Chitimazat had been forbidden by the local priest, but when he left it was again performed. In the early part of the twentieth century, the local priest confiscated the deer and jaguar skins and permanently banned the dance. After that only the more Christianized Calanmazat dance was performed.

Although the text and the costumes in the Deer Dance became Christianized, many of the most important elements of the dance retained their pre-Hispanic significance. Lise Paret-Limardo writes:

The dance was, therefore, always dedicated by the indigenous people to their deities, as the K’iche’s still do to the God of the World (Dios del Mundo) and the Tz’utujiles to the God of the Hill (Dios del Cerro). Later, the evangelizers consecrated it to the patron saints of the towns, or they transferred it to the dates of Christian religious festivities, ending up modifying it, until elements of the Catholic creed predominate in the texts recited by the dancers; but the dance still retains some of its primitive attributes, including rituals, preceding or interspersed, of the pagan form. 2

The Deer Dance, because it is a ritual about the hunt, has long been rooted in Maya spirituality where the deer is one of the archetypal animals. There are shrines outside of towns around Lake Atitlan where even today hunters perform rites where they ask permission to hunt, and where afterwards they return the bones of the deer or other animals.

Any dancer achieved status in their community by participating in the Deer Dance, or any of the masked dances. It was a considerable expenditure of time, energy, and money (if rented costumes were used rather than the older practice of using animal skins). To rent the costumes, before the construction of the Pan-American Highway, the dancers and the dance master would walk to the nearest morería.

Morerías are places where the masks and costumes can be rented. They are an institution, possibly pre-Hispanic but certainly flourishing by 1850, that is unique to Guatemala. Most morerías have been in the same family for generations. The father, who usually runs the business, is the mask maker. The costumes reflect gaudier versions of Spanish military attire in the 17th and 18th centuries. They are made of imported materials: velvet, satin, gold and silver braids, mirrors, and feathers. The Maya residents of the towns, for whom these dances were the highlight of the year, loved these spectacular costumes.

Before the dancers travel to the morería to bring back the masks and costumes, which for San Pedro la Laguna was in Totonicapán, a two-day walk, they perform rites that may include fasting and sexual abstinence. The spouses of the dancers would be included in this ceremony, and in some communities, both husband and wife would pledge not to have sexual relations until the last performance of the dance has happened. An aqj’iij, or Maya day-keeper, would be consulted to bless the trip and select the appropriate days for the trip. On their return, they would be greeted by relatives, and large firecrackers may be set off to communicate with the cosmos. A ceremony with incense (pom)and food, blessing the costumes and thanking the ancestors would be held. In many communities a ceremony dedicated to the gods, with the dancers dressed in their costumes, is held in a sacred site outside of the town before the dance is performed. On the day of the dances, the performers and musicians hold a ceremony at the house of the dance master, briefly praying to each of the four directions.3

Luis Luján Muñoz states in his book Mascaras y Morerías de Guatemala (Masks and Morerías of Guatemala):

… although it might appear at first sight that masks today have no religious meaning and are used merely for amusement, in fact their use still has a profound magical-religious character possibly deriving from pre-Hispanic times. 3

The purpose of the mask is to transform the dancer into another being. There is much ritual drinking involved in the performances, and dancers report being in a trance where the spirit of the animal they represent takes over during the dance.

In most communities, in the Christianized texts of the dances, the narrative of the dance explains that the hunters, who are Spaniards, wish to have a celebration to honor Jesus and want to trap a deer for this celebration. They go to the mountain to ask an old man to perform the necessary ritual to capture the deer. What is not obvious to the Catholic priests is that the old man represents the ajq’iij, or Maya spiritual guide, who would perform the necessary rituals for a propitious hunt. The irony is that the Christian Spaniards must consult a Maya ajq’iij to receive permission for the hunt.

We are fortunate to have the entire text of the script of the Deer Dance from San Pedro la Laguna, where nearly every speaker mentions “blessed Jesus” (in 67 out of the 89 lines delivered). Except for the captains, the hunters all have allegorical names: Shotgun, Trap, Spear, Arrow, and Swain. Here is the conversation where they ask the old man to perform the ritual necessary to capture the deer:

Swains: We want to celebrate today’s actions for my Sacred Jesus.

The Old Man: And did you bring all the necessities, the candles and incense?

Swains: Everything is here ready, Mr. Elder. Please do us favor.

The Old Man: I have no holy water, then.

Swains: Blessing. Blessing.

The Old Man: Aha! Sprinkling, holy water, and more holy water.

Then, in this strange and telling exchange, the old man (the ajq’iij) pretends not to know how to make a blessing, but then does it facetiously:

Swains: Be quick old man, do not delay.

The Old Man: I don’t know how to bless.

First Captain: I will teach you: in the name of God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit to my Blessed Jesus.

The Old Man: Aha! Go then in the name of my godfather and my godmother and my two dogs, amen.

The Old Man again: The incense has already filled the mountains with smoke. I can now go to catch the deer. There it is.3

The old man twists the Christian blessing making it more inclusive and more Maya—godmother and godfather referring to the ancestors. Artist Lorenzo González Chavajay reports that his father, who officiated in the Catholic services when the priest was not in residence, would start the service asking for the blessings of the God of the Lake, the Mountain, and the Sky as the opening of the service. Of all the masked dances, the Deer Dance exemplifies the passive resistance of the Maya to the invading culture.

- Paret-Limardo de Vela, Lise. 1963. La Danza del Venado en Guatemala. Guatemala, Centro Editorial “José de Pineda Ibarra,” Ministerio de Educación Pública.

- Gage, Thomas. 1648. The English American, A New Survey of the West Indies. London, printed by R. Cotes.

- Paret-Limardo de Vela, Lise. 1963. La Danza del Venado en Guatemala. Guatemala, Centro Editorial “José de Pineda Ibarra,” Ministerio de Educación Pública.