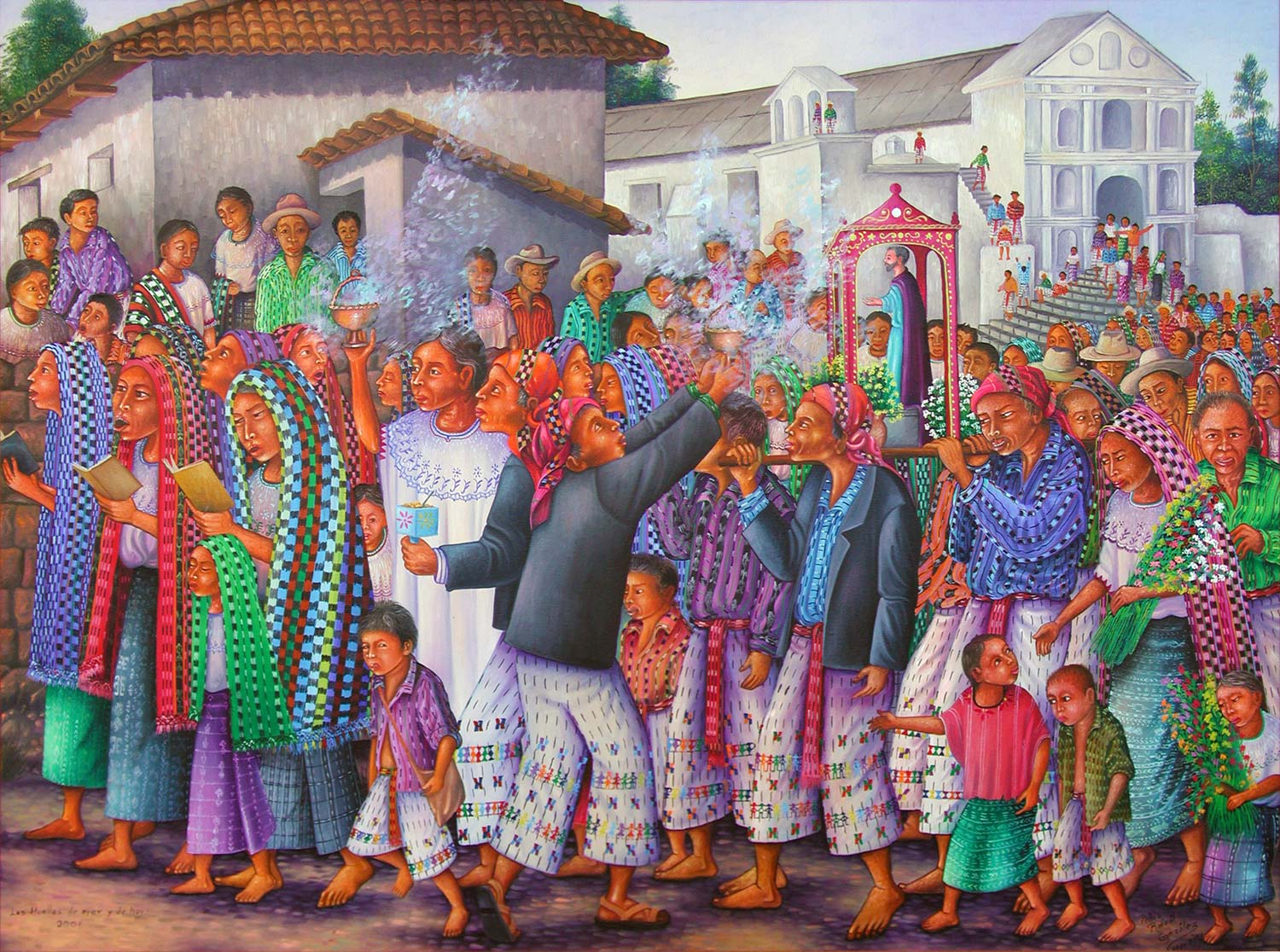

Panel 3: Catholic Church Traditions, Cofradías

In the third panel, the women singing are texeles (female members of the cofradía), followed by more principales with pom (incense) and carrying the image of Saint Peter, who has been removed from his niche in the church for the procession. The cofradías are in turn followed by members of the congregation.

Although Pedro Rafaél depicts nearly sixty people in the whole procession, each person in the painting represents several individuals. Each of the San Pedro’s six cofradías would be represented in the procession.

The Imposition of the Cofradía Religious Brotherhoods

To fully understand the triptych Footsteps of Yesterday and Today, we must understand the past as well as the recent past. Particularly important are the disintegration and fissures caused in the Maya cultural system by the imposition of the Christian religion. We must also understand how society functioned throughout the centuries since the invasion of Europeans. The role of the cofradías, or religious brotherhoods, is a key element in this process.

In the sixteenth century religious cofradías were introduced in Guatemala to help implement the Catholic faith. They quickly became popular. Because the cofradías were strictly segregated (the Spanish had their own cofradías in Antigua and Guatemala City), the Maya found that in a cofradía they could continue to perform many of their pre-Hispanic rituals in the name of a Christian saint. The Cofradía of Concepción was established in San Pedro on January 7, 1613 (Orellana 1984). To put that in a historical perspective, the first known cofradía was established in San Pedro 163 years before the United States became independent from England.

Cofradía is a Spanish word that implies brotherhood, but both the cofradías and the civil government operate on a system that would better be called “fatherhood.” As Benjamin Paul has explained many times, in the Tz’utujil language, if one is a male, there is no single term for one’s brothers. There is a term for one’s older brothers, and another word for one’s younger brothers, and a word for one’s sisters. Likewise, if one is a girl, there is a word for one’s older sisters and another for one’s younger sisters, and a word for one’s brothers. The language performs two functions: it helps establish a hierarchy (one does what one’s older brother commands); and it also denotes a separation between male and female roles. This strict hierarchy also exists in the civil government and the cofradías; i.e., the cofradías have a ranking of importance in relation to each other; and the members of each cofradía have a ranking within that cofradía. (Paul 1989)

There were six cofradías in San Pedro. Each cofradía revered a particular saint. At the head of each cofradía, was a cofrade, whose assistant was called a juez; five mayordomos; and three unmarried women called texeles or Te’xelaa’. An image of the saint was kept on an altar in a separate room in the house of the cofrade. It was the duty of the cofradía to keep fresh flowers on the altar, and keep the floor covered with pine needles. The texeles ground castor oil beans from which they obtained oil for a lamp that was kept perpetually lit on the altar. During the year, the cofradía would be responsible for a festival honoring their saint. Each cofradía was responsible for one day of the week. They would be responsible for burying anybody in the community who died on that day. All these expenses, which were considerable, would fall on the cofrade.

Protestantism attracted many Maya because it opposed drinking. Ritual drinking had been a part of the cofradías since their inception. Just as in other small Maya towns, there had been no resident priest since the previous century, but only a visiting priest and local Maya who performed the services. Catholic Action began sending resident priests in hope of reforming the church enough to keep members from leaving. Benjamin Paul observes (Paul 1996, 4):

The death blow to the weakened cofradías came in 1970, when the then resident priest, a Carmelite from Navarre, excoriated cofradía members from drinking in church on Sunday, as they had done ceremonially from time immemorial, and denied them various customary privileges. In effect, they were excommunicated.

San Pedro once had a unified face it presented to the world. In the civil-ceremonial system the townspeople had a well-established way of gaining respect as they progressed through life. If they earned the title of principale by the end of their lives, people would kiss their hands as a token of respect. The church and the government functioned together as part of a whole.

Now, besides the Catholic Church, there are scores of fundamentalist Christian churches in town. Even in families considered progressive, children have been disowned by switching from one church to another. The competition of political parties during elections has become rancorous, and occasionally violence has resulted during the election process. The unified Tz’utujil Maya society has broken into the three separate parts represented by the three panels of Pedro Rafaél’s painting: the masked dance, representing the pre-Hispanic Maya heritage, the government, and the Christian religion.